US nuclear fears delayed Moldova's Independence, ex-FM says

The independence of the Republic of Moldova wasn't just delayed by pressure from Moscow, but also by the strategic interests of major powers.

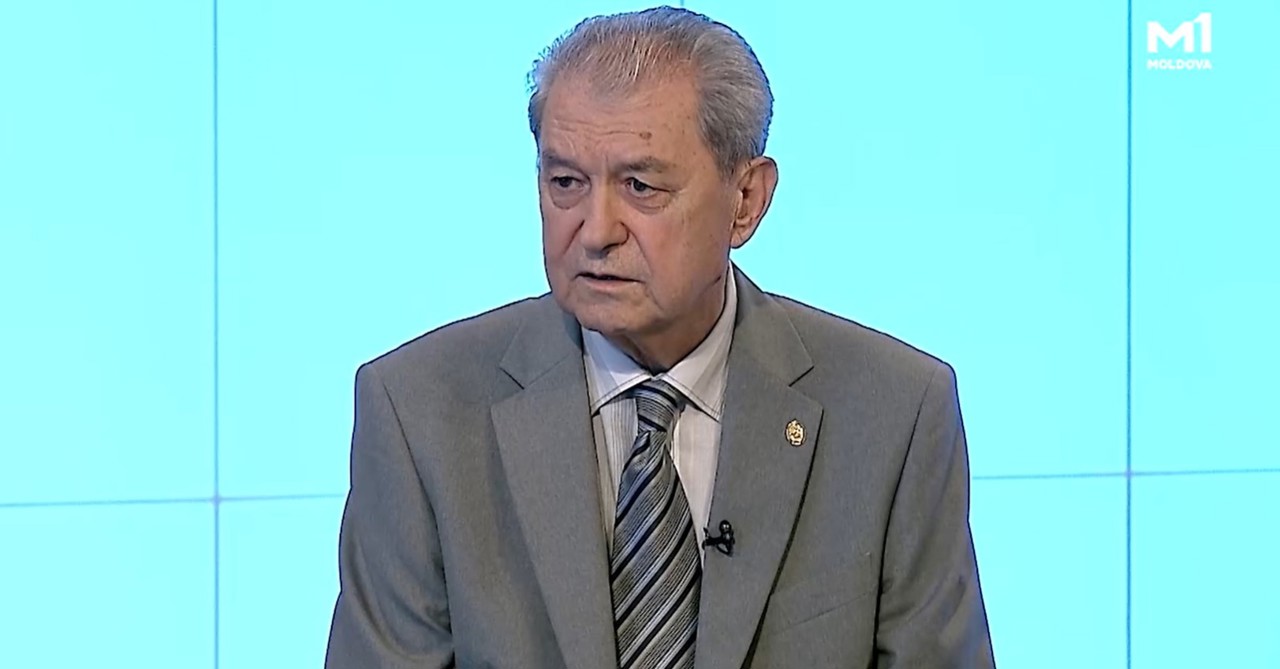

The U.S. and its Western Allies didn't immediately back the liberation movements of the Soviet states, fearing nuclear instability. Nicolae Țâu, who served as Foreign Minister from 1990 to 1993 and was the first Ambassador of the Republic of Moldova to the U.S., revealed on Moldova 1 that the Baltic states were exempted as part of a financial agreement guaranteed by the West, while Moldova's path to independence was an arduous one.

The Declaration of Sovereignty: The first step toward independence

Nicolae Țâu was confirmed as Foreign Minister on June 6, 1990, shortly before the Declaration of Sovereignty was voted on June 23, 1990. This was the moment the Republic of Moldova embarked on a challenging path toward independence.

"That declaration already stipulated that we had the right to establish international relations with other countries, so we had more opportunities to promote the foreign policy of the Republic of Moldova," Nicolae Țâu recalled on the show "Dimensiunea Diplomatică" (The Diplomatic Dimension) on Moldova 1.

According to the former head of Chișinău's diplomacy, the first step was to establish diplomatic relations with Romania, and he traveled to Bucharest for a visit.

"I spoke with the then prime minister and went to Bucharest. I called the Soviet Union’s ambassador, and he asked me, 'But what do you want to discuss?' When I arrived, I told him I wanted to arrange a meeting with Romania's foreign minister. They arranged it (...) The next day, I went to the Ministry of Foreign Affairs; we met with the state secretary, Mr. Neagu. I informed him what we wanted—for our children to study in Romania, to have good cultural relations, because until then it was even forbidden, hidden. They said they had no problem with it, only that it depended on what Moscow would say, because we were in the Soviet Union, but they were in socialist Romania," the former minister recounted.

At that time, according to Nicolae Țâu, the necessary steps were taken to abolish visas, even though all procedures were coordinated by Moscow. "I returned home, called Mr. Eduard Shevardnadze, the Soviet Union's foreign minister, and he told me he would expect me at 3:00 p.m. the next day. He immediately gave instructions for us to have passports; he said 10-15 thousand, and then we would see. I asked him to organize a consulate in Iași, Romania, because someone had to take care of our students, and he agreed. So, this was practically the first step toward what is considered reunification, because it brought people closer to each other," the former ambassador observes today.

The Baltic States: Liberated at a price, but not Moldova

When Eduard Shevardnadze, the Soviet Union's foreign minister, announced that it had been decided to grant independence to the Baltic states, Nicolae Țâu had the courage to ask if the Republic of Moldova would follow the same path. "I'm informing you: Mikhail Gorbachev (the last leader of the Soviet Union) has given his consent for the Baltic states to become independent. - Yes, there are three of them. Does that mean we'll be the fourth? - No! Some solutions will be proposed to solve all problems, and you won't want to become independent," Eduard Shevardnadze replied, without offering details on the actions that would be taken.

Soon, the explanation was offered in London: independence for the Baltic states came at a price. "Immediately, Romania's Ministry of Foreign Affairs organized a visit to Great Britain, Italy, and the UN. The first visit was to Great Britain. I met with Douglas Hogg (a British politician and lawyer who from 1990 to 1995 was Minister of State for Foreign Affairs) and, while discussing, he told me that a decision had been made: the European Economic Community and the United States would grant the Soviet Union an aid package of $12 billion. In return, the Soviet Union would release the Baltic states," Nicolae Țâu recounted.

When the diplomat requested the same support for Moldova, the British response was laconic. "Now, we cannot recognize you. He made it clear to me that the United States was against it and that's why no one would recognize us. I said: Georgia and Romania have recognized us. He replied: You are related to Romania, that's why it recognized you, but in principle, no one else will recognize you," the British official told the head of Chișinău's diplomacy.

Risks to nuclear stability

On November 7, 1991, Nicolae Țâu was in the U.S. to seek support. He had meetings with officials from the Department of State, the National Security Council, and the U.S. Congress. The reactions were, for the most part, negative:

"They said that we had to remain in the Soviet Union, and there were no other arguments. But I met with Lee H. Hamilton, the chairman of the U.S. Congressional subcommittee (Lee H. Hamilton held key positions in U.S. foreign policy and intelligence oversight) who told me: - you will be independent in two months."

The reason for the U.S.'s hesitation, however, was a different one—the Soviet nuclear arsenal. "When I met tête-à-tête with several officials, I was told that the main problem was the Soviet Union's nuclear weapon," Țâu explained.

The collapse of the USSR and new opportunities

Subsequently, the act signed at Belovezh Forest (in Russian: Беловежская пуща) by Russia, Ukraine, and Belarus officially formalized the dissolution of the Soviet Union. "The Soviet Union no longer received money. It collapsed. And the Americans supported it then because it was an opportunity to dissolve the Soviet Union more peacefully. To prevent other, more serious problems from happening," the former official noted.

The UN speech: The cost of diplomatic courage The Republic of Moldova joined the United Nations (UN) on March 2, 1992, the official date the Transnistrian War began, and Chișinău's hopes were that this step on the international stage would help with the Transnistrian crisis. "We became part of the UN. This showed that we were independent. We all rejoiced then. We thought the UN would help us. When the conflict started, the very first delegation that came to us was from the UN. (...) It happened that at the UN, a deputy secretary-general, Piotrowski, was on leave. When he returned, he said: no, the UN doesn't deal with such a thing, the CIS deals with it," the former official recounts.

In 1992 and 1993, Nicolae Țâu participated in the UN General Assemblies, where he openly criticized the presence of the Russian army on Moldova's territory. In the interview with Moldova 1, he suggested that this speech may have led to his resignation, in a geopolitical context where Moldova's diplomacy was trying to reconcile its desire for freedom with the interests of the major powers.

"In 1992, I spoke about the Russian Federation's army being on our territory without the approval of the Republic of Moldova. In 1993, I said it very harshly. After I spoke at the UN, the entire hall rose and applauded me. Even Ukraine's ambassador said: When will our people speak like you? The diplomatic mission of the Russian Federation filed a protest and said that this was not the position of the Republic of Moldova, but the position of the minister. I couldn't have a position," concluded Nicolae Țâu, the first Ambassador of the Republic of Moldova to the U.S.

Translation by Iurie Tataru